Can you find the Second Act?

Most stories are structured broadly into three acts. Next time you watch a movie, see if you can point to the places where the story shifts from one act to the next and how the setting and scenes in the story contributed to the story’s theme. What choices did the narrative designers make to give their characters room to grow?

Wanna cheat? Sometimes it is easier to identify acts by looking for the “act breaks,” the moments when the story transitions from one act to the next. Jump down to the section on how to recognize act breaks.

Why do we have “acts?” in modern storytelling?

Modern stories tend to time their structure into three acts with the second act being twice as long as the first or third. Each of these acts serves a function in our story.

Most compelling stories feature a main character that has to change something about herself to evolve into the person she has the potential to be. It’s this internal tension that makes stories so interesting to us: we get to feel the tension with her as she struggles (and hopefully succeeds) to evolve. Generally, each act serves a purpose in terms of the main philosophies of the movie.

Act I: We are introduced to the Prevailing Notion, but something challenges it.

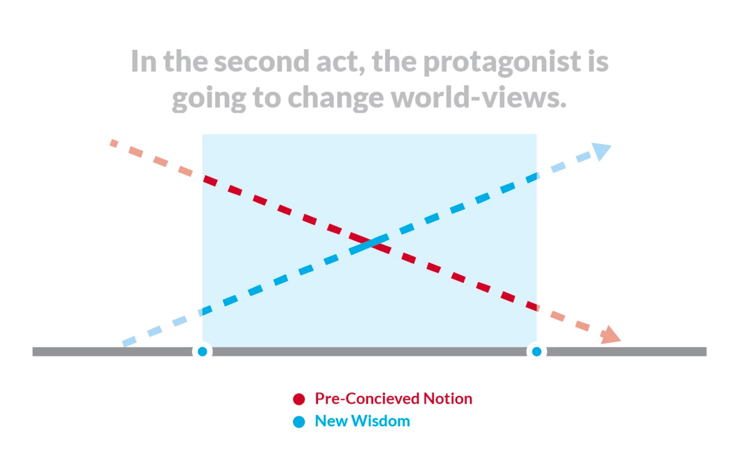

Act II: The Main Character undergoes a change in her philosophy.

Act III: The Main Character affirms the New Wisdom (usually by overcoming some sort of personal or public challenge).

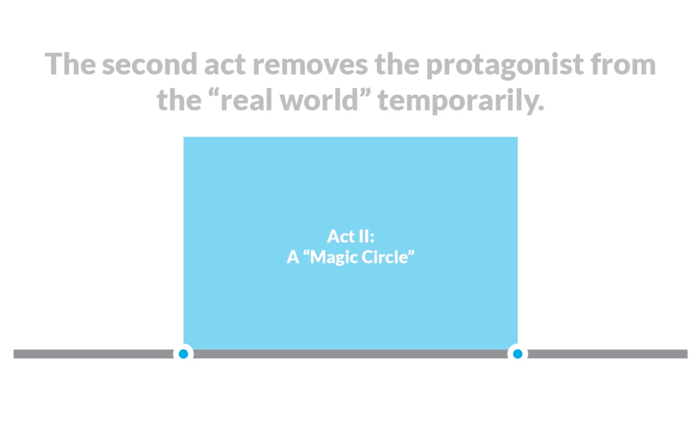

Part of the reason the second act is twice as long is because this is where the protagonist is going to do most of her learning. Stories usually create a separate space, which we call a “magic circle” to develop her skill before facing the final challenge to solve the original problem.

Act II is a “Magic Circle.”

Think about the last time you had to learn something new. It could have been simple like a musical instrument or a new way to solve a math problem. Maybe it was something difficult, like discovering you were an alcoholic, learning that an aspect of your personality alienated you from your friends, or realizing that some other aspect of your personal worldview was leading your life toward depression, chaos, or destruction.

For most of us, accepting that we have a problem and deciding to change it is the most difficult thing we can do. Let’s look at two aspects of the human experience that make change hard for us in the real world:

Transition often takes some time.

True change takes a great deal of learning, and learning takes a lot of time and patience. Learning to drive takes a lot of awkward trips around the neighborhood, becoming an artist takes a pile crumpled up paper balls in the waste bin.

Finding Progressive Challenges

(intro to this) When we’re young, teachers curate challenges that start small and get progressively harder – society’s expectations for children are calibrated to the state of their learning. The important thing about these early challenges is that they are artificial – as students we study fake problems to practice for the real problems others may depend on us to solve one day.

Antibodies in the ‘real world’ fight our will to change.

Adopting a new way of thinking or acting is difficult if we stay in the same place surrounded by the same people. Our old friends, family, places, and habits have an amazing tendency to pull us back into our old ways.

While we’re developing new skills and habits, it often helps to spend time in a different place. This space creates a fresh environment safe from the judgement of others and temptation from our old habits.

The narrative structure can give a character a little bit of help by creating a space where she can build strength away from the antibodies. This isn’t a safe space by any means – in many old stories, the protagonist quite literally descends into hell – but it is a simpler space where the protagonist can gain a clearer vision of why the New Wisdom is so important and have the chance to grow.

So now that we know what Act II is for, how can we recognize it in a story?

Recognizing Thresholds

One easy way to find where acts begin and end is to recognize the transition from one act to the next is to look for “thresholds.”

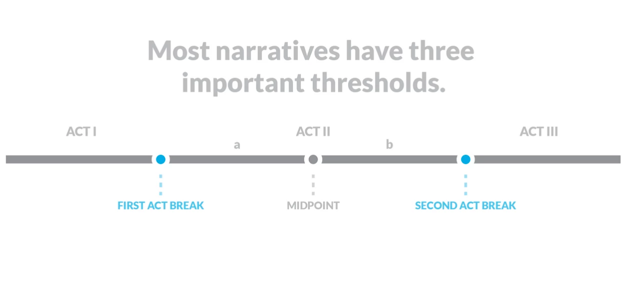

A Main Character passes a Threshold when she makes a critical decision that moves the story forward. There are three important thresholds: The First Act Break, the Midpoint, and the Second Act Break. They are usually equally spaced through the story.

We like to note three important thresholds that can be found in most stories. We already discuss one of these, the midpoint, in a previous article. The other two mark the transitions between the acts. We’ll discuss the significance of each of these thresholds later, but for now, here are some hints that a threshold is being crossed.

Hints…

Some hints that we’re in the First Act Break and about to pass into the Second Act may be:

- The character has recently lost someone/something that was holding her back.

- The character(s) are changing location or embarking on a journey.

- We’re about 1/4th through the movie (so 15 minutes into a 90 minute film, for instance)

Some hints that we’re in The Midpoint might be:

- The Main Character or the Protagonist has just realized something profound about the conflict that she didn’t know before.

- The Main Character makes a commitment to herself to learn the New Wisdom.

Some hints that we’re in the Second Act Break and about to pass into the Third Act may be:

- We’re changing location again. We might be coming back to the location in Act I, or going to a third place.

- All of the key characters will be in the same place at the same time to finally confront one another with the problems we’ve seen unfold through the movie.

- We’re entering scenes with a lot more people in them. This could be a final battle flying through a city of the big, awkward wedding in a chick-flick.

- We’re about 3/4ths into the movie (so 75 minutes into a 90-minute film)

What’s Next?

Consider some more complex applications of Magic Circles in the Think About it questions below. When you can see the roles that the three acts and the three major thresholds play, move on to lesson three where we explore how narrative designers can use these ideas to craft the decay of the prevailing notion and growth of a new wisdom gradually over the course of a story.

Think About it…

In Act II, narrative designers give characters the time, space, and group of people they need to learn new skills and accept a new philosophy. One way to think about this is to think about Magic Circles, places where new rules

Magic circles in real life

There are many ways in real life that we create “magic circles” – places where the old logic, reasoning, or simple unforgiving nature of the real world is suspended to give us a chance to explore. What Magic Circles can you think of in the real world?

(some examples may be sound-proof rooms for practicing musical instruments, brainstorming sessions for coming up with new ideas, practicing your tennis stroke against a wall, playing “make believe with your kids…)

Thresholds

We tend to mark the entry and exit of a magic circle with certain architectural features, rituals, and other indicators. How are Thresholds marked in the real-world magic circles you thought about?

Progressive Challenges

Act II often constructs an learning environment for the main character where she confronts progressively intensifying challenges. Think about the last skill you successfully learned: what challenges did you face in the beginning? What felt like the most important turning point for you? How did you know when you “made it?”

Notes

(1) For more on this, check out Duhigg’s The Power of Habit

(2) What we call “The First Act Break,” Joseph Campbell identifies as “Crossing the First Threshold” in The Hero’s Journey.

“With the personifications of his destiny to guide and aid him, the hero goes forward in his adventure until he comes to the ‘threshold guardian’ at the entrance to the zone of magnified power. Such custodians bound the world in four directions — also up and down — standing for the limits of the hero’s present sphere, or life horizon. Beyond them is darkness, the unknown and danger; just as beyond the parental watch is danger to the infant and beyond the protection of his society danger to the members of the tribe. The usual person is more than content, he is even proud, to remain within the indicated bounds, and popular belief gives him every reason to fear so much as the first step into the unexplored. The adventure is always and everywhere a passage beyond the veil of the known into the unknown; the powers that watch at the boundary are dangerous; to deal with them is risky; yet for anyone with competence and courage the danger fades.”

We like Campbell – Kyle, in particular, is a huge fan of his later lectures collected in the book Myths to Live By. Like others, though, we view his concept of Monomyth a little rigid – useful for what it is, and full of great insights, but certainly not a one-size-fits-all method for narrative design. We like to call it similarities whenever we can, though, because it is such a well-known model and it has greatly influenced both the way we see story and some of the common labels we like to use.

(3) Our Second Act Break is Joseph Campbell’s “Return Threshold.”

“The returning hero, to complete his adventure, must survive the impact of the world. Many failures attest to the difficulties of this life-affirmative threshold. The first problem of the returning hero is to accept as real, after an experience of the soul-satisfying vision of fulfillment, the passing joys and sorrows, banalities and noisy obscenities of life. Why re-enter such a world? Why attempt to make plausible, or even interesting, to men and women consumed with passion, the experience of transcendental bliss? As dreams that were momentous by night may seem simply silly in the light of day, so the poet and the prophet can discover themselves playing the idiot before a jury of sober eyes. The easy thing is to commit the whole community to the devil and retire again into the heavenly rock dwelling, close the door, and make it fast. But if some spiritual obstetrician has drawn the shimenawa across the retreat, then the work of representing eternity in time, and perceiving in time eternity, cannot be avoided.”